Suzanne, Serena and the Hidden Threads of Tennis Style

Two legends, a century apart, shaped tennis style forever. As the French Open kicks off, how well do we really know their influence - and the surprising ways it still shows up today?

Part I - "Gay, brittle and brilliant.”

99 years ago, on a sparkling September afternoon in Paris, a 768-foot ocean liner pulled into the city’s main port. It entered France empty and departed for the US with 1.5 tonnes of cargo, 12 carts of mail and 1,600 passengers. One of these passengers, staying in a newly appointed first-class cabin, was the era’s greatest ever tennis player: Suzanne Lenglen.

Lenglen was off to New York, where she would embark on a national tour of the US, drawing thousands of fans by train, car, and horse-drawn carriage to watch her play.

To look back now is to see that Lenglen wasn’t ahead of the time so much as existing outside of it. A gravitational force so mesmeric she could lure 13,000 to Madison Square Garden and help establish tennis as a paid profession (for both men and women) in the process. In diving into Lenglen’s legacy, there is a YouTube video that I’ve returned to time and time again. It distills her mastery of tennis into a scratchy, 16min film, replete with the patina of old-world style:

That video, while an amazing artifact, doesn’t even capture the true extent of her talents. She was “The Goddess of Tennis” as anointed by The New York Times. “The player for the Jazz Age: gay, brittle, and brilliant.”

Once you shake off that gloriously old-timey description (it practically begs to be read over a crackling radio), you begin to realize: no one invites comparisons to jazz - in all of its style and verve - through their on-court play alone.

The real clue to Lenglen’s stunning popularity lies off the court, with her departure to New York on that September morning offering the most incisive example of why the world loved her.

Because on the very morning she was set to travel to the US - before the matches, before the fanfare - a journalist approached her and asked about her fitness:

“I don’t know,” she replied. “I haven’t played for months.” Instead, she said, she had been shopping. “You should see this black and white evening dress of mine. It’s a masterpiece.”

Because while Lenglen’s athletic accomplishments stand alone (seven years as the world No. 1, six-time singles title winner at Wimbledon, two-time winner of the ‘triple crown’ at the French Open, gold medalist at the 1920 Olympics), the full rendering of her charm is only revealed once you start to sketch out her influence on fashion.

Lenglen reinvented restrictive corsets and petticoats (the fashion order of the day under the strict objective of ‘modesty’ for all female athletes), causing a sensation at her 1919 Wimbledon debut with a low-cut dress and rolled stockings, frequently deemed as "indecent" by the press.

Soon after, she introduced her signature bandeau headband: two yards of colorful silk chiffon, sometimes polka-dotted or diamond-adorned, even color-coded to match the round.

The popularity, and shortness, of her hemmed skirts flipped perception of tanned skin, from a matter of scorn to one of aspiration (for better and mostly worse). The knock-on effect she started led to a renaissance in the design of swimsuits, ultimately resulting in greater and greater amounts of exposed skin.

Her trademark white plimsolls inspired unisex “Lenglen shoe” spin-offs – a precursor to the later ubiquitous Stan Smith – which retailers called “light, elegant, and practical”. While the British tailor John Redfern was the first to design sportswear specifically for women in the 1870s, it was Lenglen and the more androgynous, comfortable fits later popularized by Coco Chanel, that saw it take hold.

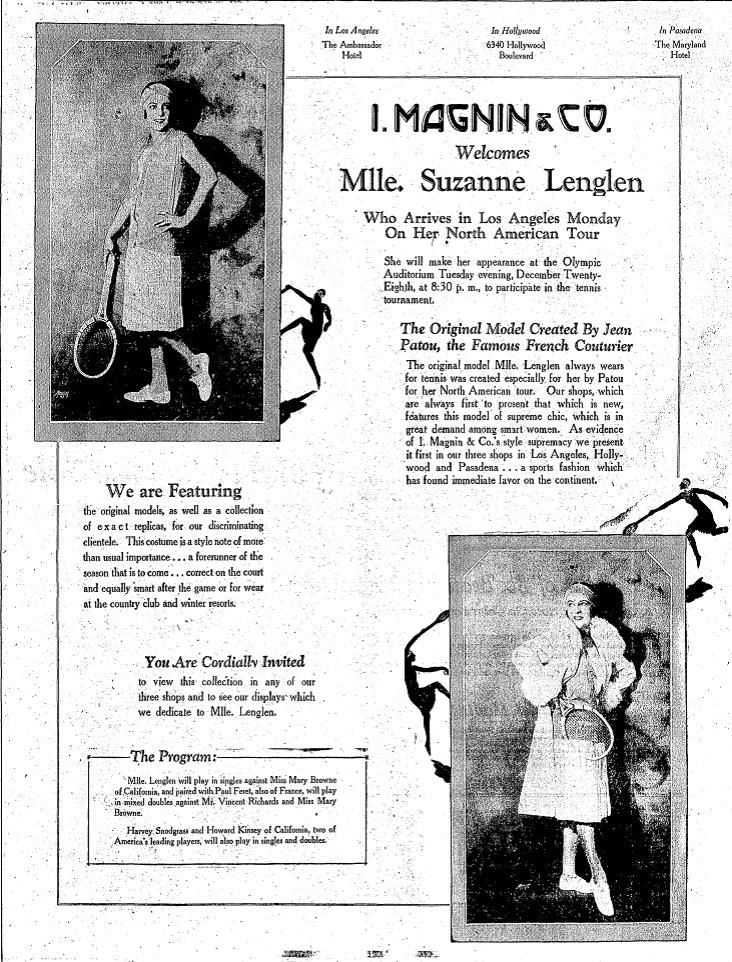

It wasn’t just her clothing choices which defied convention, but the behavior that accompanied them: ermine stoles while walking in pre-match, floor-length fur coats while sipping cognac post-match. As muse to Parisian couturier Jean Patou (who designed her on- and off-court wardrobe), Lenglen became the face of avant-garde sports style. By 1926, when Queen Mary presented her with a medal to mark Wimbledon’s 50th championship, it was Lenglen, not the monarch, who was the global fashion icon.

To witness her move through the world at that time would be to assume there would never be another like her. A tennis prodigy with near-unbeatable control and speed, and a fashion revolutionary whose idiosyncratic style reshaped how the world dressed.

Lenglen, as they say, was a once-in-a-lifetime character. It was a description as prescient as it was true. For it took another whole lifetime, another whole century, for the world to witness another like her.

Part II - "I call it a corset dress. Very Hollywood glamour with the silk."

It’s March 2004. Key Biscayne, Florida. The heat is stirring but not yet stifling. 78 years since Suzanne Lenglen’s historic tour of the US, and 66 years since she passed away. The not-yet-greatest tennis player takes to the court in a Round 1 match at the Nasdaq 100 Open in front of a few hundred onlookers. It’s her first match in nine months after serious knee surgery. Her outfit reflects her state of mind - confident, renewed, strong - and her newly signed contract with Nike.

She’s sporting the first piece they will make together: a white silk dress with a billowy skirt (with matching warm-up coat, all dry-clean only). Cinched tightly at the waist with a wide silver corset, exaggerating the shoulders and back, everything is tailored for unrestricted movement and maximum-speed groundstrokes.

“I call it a corset dress,” she said at the time. “Very Hollywood glamour with the silk."

Around her head, she wore a scarf that displayed one name, her name, in rhinestones. While it was Serena the crowd saw, the items themselves, when brought together, called to mind an icon of a different era. One who also donned corsets and headbands while dominating her opponents with power and precision: Suzanne Lenglen.

Williams would go on to win that match, and thousands more. She would win everywhere, all the time, while wearing everything and everyone. She would win in catsuits, leather boots, Off-White tutus, backless denim skirts. She would win in outfits perfect for a woman with a racquet in one hand and a script in another.

Each ensemble told a new story. Take the neon yellow dress she wore at the 2015 Australian Open, one that featured daring cutouts on the lower and upper back.

"You can be beautiful and powerful at the same time," she said at the time. "This whole year is about the back and strength and women and power. We wanted to look at my back all year, so all year you'll be seeing my back!"

Before “eras” were neatly packaged and sold as stadium tours, Williams was living them.

Part III - “I will never take my daughter to watch robots play tennis.”

June 2024. Alexis Ohanian, Serena’s husband, is on stage in Cannes. I am, sadly, on the couch at home. He’s speaking to a small crowd of ad folk about the impact of AI creative industries.

Eventually, the conversation turned to sports. I watched him sit up a little in his chair, edging closer to the crowd and the camera in front of him:

“AI will evolve the way we consume content in ways we barely understand. But we have a part of our humanity that needs to feel something human…and no matter how good those robots get, you will never want to see robots play tennis, I will never take my daughter to see robots play tennis. So if you’re wondering why I’m investing so much money into sports, and women’s sports in particular, it’s because of this: 10 years from now, live sports will be even more important to us, because it will be the one thing to connect us to our own humanity when we want to be entertained.”

There’s a lot in that, but to pull out one thing: it’s clear that when Ohanian speaks about the humanity and entertainment within sports, he could have equally been talking about Suzanne Lenglen as much as Serena Williams. Icons of two different centuries, bound not just by tennis and trophies, but headbands and haute couture.

Each was an incessant target of the press. Labels like 'indecent’ and ‘attention-seeking' were lobbied at both. But both pushed through, never letting their personality (and by extension, their style) be dulled by those that couldn’t see athletes as being anything more than a series of skills executed on a court.

And now? It couldn’t be more different.

Tennis players headline Paris Fashion Week. Jannik Sinner is front row at Louis Vuitton. Coco Gauff just launched a capsule with New Balance and MiuMiu. Naomi Osaka has her own label, Kinlò. Roger Federer is a Uniqlo ambassador and a co-owner of the running brand On. The fashion-tennis overlap isn’t a subtext anymore, but the main plot.

It’s only in looking back at the legacies of Suzanne and Serena that we can start to see their influence in full fidelity; harbingers of a future where tennis and style are as intertwined as the strings of a racquet. Pulled ever tighter by forces of their own making, to the point where we now scarcely see them apart.

Spot on Max. I was on someone else's post today and they made a similar comment to you. The public won't pay to watch computers play chess but they will for a child prodigy. The population want to see the human stress, emotion and human brilliance that only a human star can exude. Never a robot or computer. AI will not do everything and won't replace human fascination of other extraordinary humans beings.